Wind Surgery

Wind Surgery is the term applied to a collection of procedures which aim to improve the function of the horse’s upper airway. The terminology is confusing and often misunderstood by owners and trainers so please read on for a full explanation!

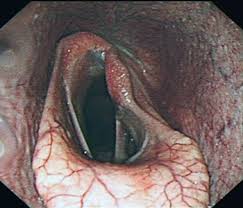

A normal equine larynx

Laryngeal Function

The horse’s larynx is located at the junction of the nasal passages and the trachea or windpipe. It acts as a valve, regulating the amount of air that passes to the lungs; at rest, the horse has a very low oxygen requirement and so the larynx is barely open. As he begins to exercise, the larynx opens to allow more airflow. When at full gallop, our equine athlete must maintain his larynx in the fully open position to ensure the maximum amount of oxygen gets to the lungs, but also that carbon dioxide, the waste product of respiration, is evacuated from the body. The movable parts of the larynx are the vocal cords which are controlled by the dorsal laryngeal muscles which in turn are stimulated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve. In horses, the nerve on the left side of the body is often dysfunctional and prevents the individual being able to hold the left vocal cord in the open position; as the horse tires, the left cord collapses into the midline of the larynx and may even occlude the entire airway. This clearly has the effect of starving the animal of oxygen and preventing removal of carbon dioxide, so he can no longer maintain a gallop. This condition is called left-sided laryngeal hemiplegia and it causes the horse to make a continuous inspiratory noise ranging from a whistle, in mild cases, to a roaring sound in severely affected animals. The surgical options to correct the problem are either a Hobday procedure, which involves removing the left vocal cord and the sac behind it, therefore removing the tissue that collapses into the laryngeal passage or else a tie-back operation which as the name suggests, uses a permanent suture to tie the left vocal cord in a fully open position so that it cannot collapse. The latter, is the more successful procedure but it is not without its complications; some horse cough following the tie-back due to small particles of food ending up in the windpipe as the swallowing mechanism has been interfered with, and sometimes the suture can break or slacken off so that the larynx is no longer fixed open. Often a Hobday is performed in addition to the tie-back so that if the suture does slacken, there is minimal tissue to obstruct the laryngeal passage. Although technically easier to maintain asepsis when operating under general anaesthesia, some surgeons perform tie-back surgery in the standing horse. This option does rely on having a compliant patient but does seem to be gaining in popularity.

The Hobday surgery is traditionally done under general anaesthesia using a scalpel but it can also be done in the standing sedated horse using a surgical laser passed up an endoscope.

A larynx showing left-sided paralysis

A patient undergoing tie-back surgery at Peasebrook

soft palate dysfunction

Aside from the larynx, the other part of the horse’s airway that under performs and is often subject to surgical intervention is the soft palate. This is a floppy piece of tissue that is located at the back of the hard palate or roof of the mouth, and separates the oral compartment from the nasal passages at exercise. The soft palate comprises a muscular layer overlaid with mucous membrane, similar to the lining of the mouth or nose. Soft palate problems arise only at strenuous exercise when the muscular component of the structure fatigues, just like any muscle does. As fatigue sets in, the palate changes from being a relatively stable platform to being a very unstable piece of tissue resembling a billowing sail. Eventually the palate becomes displaced upward from its position of dividing the oral and nasal passages so that now the horse is breathing via his mouth, something that nature did not intend the horse to do; this usually results in a gurgling noise and the horse often slows dramatically and is consequently pulled-up by the jockey. As the horse slows down he usually swallows and then the soft palate returns to its normal position. This is why soft palate problems can only be diagnosed when the horse is being strenuously exercised, hence the need to examine him with a scope on a treadmill or using the over ground scope system on the gallops.

Dorsal displacement of the soft palate; compare with the image of a normal larynx above.

A horse fitted with the overground endoscope to record upper airway function at speed.

soft palate treatment

A large number of horses will show signs of soft palate dysfunction secondary to other factors; it is common in youngsters that are just immature or not fully fit. It can be brought on by heavy ground conditions which lead to early fatigue, viral infections, muscle dysfunction also known as tying-up, cardiac problems such as atrial fibrillation or any orthopaedic problem resulting in pain or lameness. The take home message here is don’t rush in to surgery before ruling out any of the above initiating factors of soft palate displacement.

Conservative management consists of making sure the horse is in perfect health, is fully fit and free from lameness. He should be raced on good ground and should not be made to front run i.e. conserve his energy until the final stages of the race. A drop or crossed noseband should be fitted to keep the horse’s mouth closed; it is postulated that if the horse opens his mouth during racing and allows in a lot of air, this can upset the apposition of the soft palate with the base of the tongue and thus induce some instability of the soft palate. The same philosophy applies to the tongue-tie which aims to maintain the position of the base of the tongue.

If conservative management is not successful and it is deduced that the horse has a primary soft palate dysfunction then surgery is the only option. Unfortunately no one surgical procedure achieves a success rate of anything much above 70%. Palatal Cautery which simply involves burning the oral surface of the soft palate aims to produce significant scar tissue and hence a stiffening of the tissue making the billowing sail behaviour less likely. This is currently the most widely adopted technique in the UK and is favoured because it is very easy to perform, carries little risk and the horse can remain in training. It is a pretty crude procedure but it does seem to produce results however they may be short lived (9 to 10 months) and so the surgery often needs to be repeated.

The other common surgical intervention for soft palate displacement is the tie-forward operation. This surgery evolved as a result of the success of a device called the Cornell collar which was developed by a very forward thinking vet called Norman Ducharme in the USA. The collar lifted the horse’s larynx up and forward causing a greater overlap with the soft palate and so preventing the palate being able to displace out of its normal position. The results with the collar were very encouraging and so Ducharme devised a surgical technique to mimic the same effect. The tie-forward literally pulls the larynx forward and upwards within the head using wire anchored to the basihyoid bone. The success of the surgery can be measured by taking x-ray images before and after to measure the change in position of the larynx relative to the other structures.

Another theory regarding soft palate dysfunction suggests that the larynx actually moves backwards due to contraction of a group of muscles in the horse’s neck called the sternothyrohyoid muscles and this allows the palate to displace upwards. Cutting this muscle group thus prevents this backward movement of the larynx occurring and is certainly effective in some cases.

The future of laryngeal and soft palate surgery in the horse is thought to lie with the implantation of neuro-muscular stimulators which function rather like a pacemaker.

Since left sided laryngeal hemiplegia results from a defective nerve/muscle unit it makes sense to replace this with an electrical implant which can initiate muscular contraction. This has already been achieved by Norman Ducharme and his team including Justin Perkins of the Royal Veterinary College, experimentally but is not yet commercially available. It is also highly unlikely that the Jockey Club will ever allow horses to race with such a device in the UK. Recently, Justin Perkins from the RVC and Fabrice Rossignol from the Clinique de Grobois in France, have re-visited the surgical option of re-innervating the defective laryngeal muscle, the cricoarytenoid dorsalis (CAD) using a branch of the first or second cervical nerve. This surgery was performed back in the 1980s and 90s with poor success rates, however an improved technique is giving excellent results and is sure to become the first choice surgery to correct laryngeal paralysis. Justin Perkins is also fitting the neuro-muscular stimulators to these patients to enhance the strengthening of the CAD.

The same theories using neuro-muscular stimulators can be applied to soft palate dysfunction; it would be much more sensible to try and strengthen the muscular portion of the palate rather than trying to cause scarring. This is technically more difficult than laryngeal implantation but is being trialed experimentally.

So wind surgery is here to stay in one form or another but hopefully you will feel more informed about the possibilities.

Treadmill testing at Hartpury College where Tim Galer investigated over 600 horses for upper airway dysfunction